(And Other Bon Mots of Writerly Wisdom)

I find myself sitting at my laptop writing an article on the craft of writing. Why? I have no idea. OK, I am a successful professional writer, but I’ve never written an essay about writing, and my conscious mind is thinking maybe it would be cool to try it. But is that really the reason?

Maybe it’s ego. That would be a terrible reason to write an article about writing. Do I really think I’m that much smarter as a writer that I can teach people something they don’t know? Do I really think I have something to say about the craft of writing that could possibly be of value to others? Perhaps. I remember being younger. I remember hungering for advice from writers who were older, wiser, and seemingly smarter than myself. Maybe now that I’m older, I can fill the role of the wise, older teacher. Harrumph. Or “Hah!” as the younger, texting generation likes to say.

But is wanting to know how to write better really why people read articles and books about writing? Or is their interest part of the western cult of personality, the nosy part of human nature that is more concerned with an artist’s personal life than with their art? Would I be better following the lead of Salinger and Solzenitzen and Pynchon, and staying in the writerly shadows, not revealing myself, so that others will focus on Lee Carlson’s work, and not Lee Carlson himself? Am I in danger of becoming another Hemingway, a writer who eventually became a caricature of himself, a man whose very public personal failings caused people to wrongly devalue his work? (And I do have many all-too-human failings.) Can readers separate the writer from his work? Or will my public personna overshadow my art?

I guess that’s a chance I will have to take. And perhaps not writing about craft is just as ego-stroking as ruminating on the craft of writing. I don’t know. People sometimes tell me I’m a good teacher. People often tell me I’m a good writer. Maybe I can put those two things together and come up with something of value, some useful advice, some bon mots of writerly wisdom that will be of help to others. Maybe. Maybe not. As for people and their voyeuristic interest in the painful, hair-pulling daily torture of a writer’s life, that’s beyond my control.

There are so many good books about writing by writers more famous, more accomplished and more prolific than I: Steven King. Ann Lamot. Gardner, Strunk and White, to name a few. I’ve read most of them. Could I really have something to add to that illustrious canon? Maybe. Maybe not. It’s worth a try, I think.

That’s the voice on one shoulder. The voice that says, “Do your part for your chosen profession, give something back, be generous of spirit.”

Then there is the other voice, the selfish voice, the voice that says, “Don’t do it! You’ll ruin your own writing! If you try to deconstruct how you write, you’ll screw up the process, you’ll start thinking too much, you’ll mess with that unknowable, undefinable, beautiful, wondrous thing we call creativity. You’ll risk poisoning the well. Don’t do it! Don’t mess with the mystery!”

I am reminded of my friend and mentor, the late Peter Matthiessen, winner of two Pulitzer prizes, who refused to ever discuss his work in progress. He was also my Zen teacher. One time he and I were sitting on his back porch, sipping coffee and talking. I brought up a book I was reading. The book was written by a neuroscientist who was trying to explain Zen enlightenment experiences by looking in a systematic, scientific way at the brain chemistry and neurological underpinnings of meditation, Peter just shook his head slowly and said, in a barely audible whisper, “oh no…”

Do not fuck with the mystery.

So I guess that’s the first thing I’d tell young writers, aspiring writers, people seeking advice on writing: don’t fuck with the mystery. Don’t listen to teachers who try too hard to explain, don’t read books that give in-depth advice on sentence structure and dramaturgy and word choice and deconstructing. You’ll just end up writing like everyone else. A very accomplished, very polished, very boring, very predictable MFA clone. Listen to your own voice. Be a visionary. Take chances. Jump off cliffs. Land with a splat. Fail. Pick yourself up again like Wily Coyote after being flattened by the falling anvil. (Ah! This writer suddenly thinks to himself, maybe that’s why I’m writing this essay about writing. I like jumping off cliffs into the great unknown, taking chances…)

What else can I tell you? Write! Lots. That advice is nothing new. But perhaps here is a slightly different take: Get as many different writing jobs as possible. I have been a magazine feature writer, a business journalist, editor-in-chief of a physics magazine, a travel writer, a movie reviewer, an advertising copywriter, a book author, a speechwriter and a scriptwriter. For my own creative enjoyment I’ve written short stories, poetry, eulogies, wedding sermons and, now, an essay on writing. And I haven’t just written, I’ve been edited, by good editors and bad editors, by professionals and amateurs. I’ve been copy-edited and fact-checked. I’ve seen my work made better, and I’ve seen my work butchered. I’ve learned to let go. I’ve learned to hold onto what matters with all my being, to fight with editors and my own nay-saying demons. I’ve learned that every paragraph, every sentence, every comma and every colon matters. And if it doesn’t matter, it has no place mucking up my writing. I’ve learned to be ruthless with the red pen. I learned that from being an editor, as well as a writer.

I always remember a specific incident from when I was a twenty-something aspiring journalist and had just gotten my first full-time magazine job. I handed in a short feature article to the editor-in-chief and in short notice received five pages of printed copy back from him, covered with oceans of red ink: deletions, corrections, strike-outs—whole sentences crossed out and new words written in their place. I was alternately devastated, angry, mortified, pissed-off, dejected, defiant. Was I really that bad? No! I had gotten a 4.0 average in my writing classes in college, been elected to the college honor society, been published in the school literary magazine! How dare he!

But I was that bad. The level of professionalism and perfection demanded in the real world was far greater than what I was expected to produce in college. I learned to listen to him, to learn from him. He was a good editor, and he helped me hone my craft. That was a lesson I’ve never forgotten.

Which brings me to my next point: surround yourself with good writers, good editors, good people. My writing teacher in college was Clark Blaise, the well-known Canadian writer/teacher who himself was a senior student of Bernard Malamud. Besides Peter Matthiessen, I have another Pulitzer-prize-winning friend, Steve Wick, who I have lunch with regularly. And I have other friends who are writers, editors, artists, photographers, designers and actors who I talk with, drink with, laugh with, bitch about the writing profession with.

On the other hand, stay away from writers. Hang out with real people. Run like hell from the stifling confines of the ivory tower. Be a rebel. Live, screw, drink, smoke, travel, spend money like a drunken sailor. Dye your hair bright red. Get tattoos.

Or don’t. Hole up in a monastery instead, be celibate, eat nothing but rice and vegetables. Shave your head. Wear a monk’s or nun’s robe so nobody can see your tattoos. Whatever you do, just don’t be boring. Do something interesting. Live an interesting life, and your writing will be interesting. The biggest sin you can commit as a writer is to be dull. For most of us, our lives are already dull enough. We read to be taken to someplace more exciting and interesting than our own humdrum, everyday lives. Giving your readers a more exciting life is a heavy responsibility. Don’t take it lightly. And if you don’t have what it takes to shoulder that responsibility, than forget being a writer and get a job in a cubicle. Whatever you do, don’t waste our precious time with dull, boring drivel. Life it too short.

And If everyone else is dying their hair red and getting tattoos and wearing weird clothes, then wear a suit, or a dress. Cut your hair short. The most important thing is be authentic. Don’t follow the crowd. Instead follow your own inner voice. Figure out who you are, because if you aren’t authentic, then your writing won’t be authentic either. It will be false; it will lack soul. You might look cool and wonderful on the outside with dyed red hair or a suit or a monk’s robe or whatever, and your writing might be cool and wonderful on the surface, but your words will be without depth, without soul, without an authentic voice that is saying something important, your writing will be empty and hollow, and nobody will care.

Figure out who you are first, what you want to say second. How to say it comes third. Most people make the mistake of concentrate on the how first, and not on the why. Figure out the who, what and why before the how. And when I say figure out, I don’t mean intellectually. Feel it in your gut. Listen to your body, your subconscious. When it really, truly feels right, then you know you’ve got it.

There. I didn’t tell you a damn thing about how to write. If you were expecting advice on the actual process of writing, too bad. Have I made you angry that I didn’t give you advice on sentence structure or not using passive verbs or what time of day to write or whether to use a pencil or a laptop? Good. Did I get you excited? Get your juices flowing? Has my opinionated nature made you want to throw your computer out the window, and me along with it? Or did it make you want to sit down and immediately start writing? Either way, good. I haven’t bored you. I’ve goaded you into action. I’ve given you ideas on how to live, and if you get that part right, the rest will flow naturally.

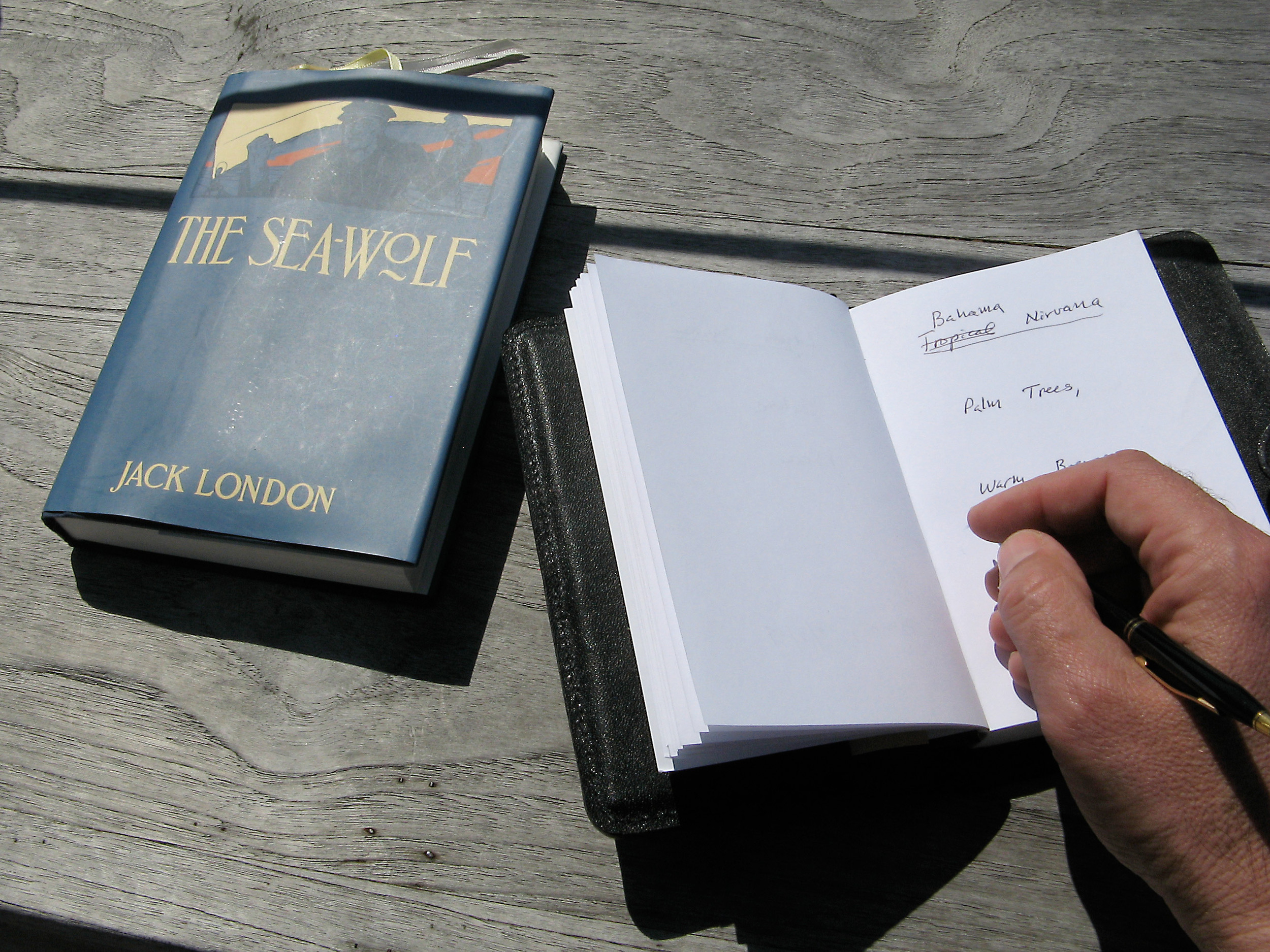

Oh, and one more thing. Forget everything I’ve just told you. These things have worked for me. But you have to figure out what works for you. I like to get out into the world. I get my stories from real life. I’m more in the tradition of Melville, Twain, London, Hemingway and McGuane: American writers who ventured out into the great sprawling, brawling terrain of a nascent world—both physical and psychological—and returned to their desks to make sense of what they found. That’s my modus operandi. But some people do better squirreled away in a garret, using nothing but their minds to create fantastic works of the imagination. That’s great; it works for them, and some of my favorite books have been written by writers such as Franz Kafka, who lived an uneventful middle-class life working for an insurance company, or Charlotte Brontë who lived the sheltered life of an clergyman’s daughter in the English countryside.

So figure out what works for you, find your own path, your own voice, your own way of writing. If you do that, everything else will fall into place with a giant, resounding “clang!”—a clear, resonant ringing of the bell that will be heard, felt and read around the world.

OTHER BLOG POSTS

-

October 2018

- Oct 29, 2018 Tree of Life, Tree Of Tears

-

April 2017

- Apr 14, 2017 RESISTANCE IS FUTILE.

-

November 2016

- Nov 22, 2016 NO GUTS, END OF STORY?

-

October 2016

- Oct 11, 2016 DONALD TRUMP, MY TEACHER

-

February 2016

- Feb 21, 2016 THE LOST SIXTH STAGE OF GRIEF: JOY

-

October 2015

- Oct 24, 2015 DON'T WRITE LIKE ME!

- Oct 5, 2015 A SOCIETAL SICKNESS

-

September 2015

- Sep 28, 2015 THE SPIRIT WORD

-

February 2015

- Feb 13, 2015 LOVE IS…

- Feb 12, 2015 FIGHTERS, YOU ARE NOT ARTISTS

- Feb 10, 2015 TO MELLOW A MOCKINGBIRD

- Feb 5, 2015 BRIAN WILLIAMS: MEMORIES, LIES & VIDEOTAPE

- Feb 1, 2015 THE ART OF SUPERNESS